Not even the world's leading nanoscientists know what nanoparticles do inside the body or the environment.

Carole Bass

July 11, 2009 - E Magazine

.....

It's a beautiful summer day. You pull on your stain-resistant cargo shorts and odor-resistant hiking socks, gulp down an energy-boosting supplement, slather yourself with sunscreen and head out for a ramble in the woods. Are you poisoning yourself? When you get home, you jump in the shower and toss your clothes in the wash. Are you poisoning the environment? Maybe.

Your sunscreen, energy drink and high-tech clothing may be among the 800-plus consumer products made with nanomaterials: those manufactured at the scale of atoms and molecules. Sunscreen that turns clear on the skin contains titanium dioxide, an ordinary UV-blocker in extraordinarily small particles. Odor-eating socks are made with atoms of germ-killing silver. Supplement makers boast of amazing health effects from swallowing nanosolutions that are completely untested for effectiveness or safety. And that stain-repellant clothing? The manufacturer won't even tell you what nanomaterials are in it.

The problem is not just that you, the consumer, don't know what's in the products you use. The much bigger problem is that at the nanoscale, common substances behave in uncommon ways. And nobody--not even the world's leading nanoscientists--knows what nanoparticles do inside the body or in the environment.

Nanotechnology, a fast-growing global industry, is essentially unregulated. Advocates and independent scientists agree that we need to get ahead of the risks before it's too late. Some call for a moratorium on the riskiest nanoproducts. Some say we just need more research, and more protection for workers in the meantime. All are worried about unleashing a powerful new technology that could have vast unintended consquences. Nanomaterials are in food, cosmetics, clothing, toys and scores of other everyday products. Yet when it comes to trying to get a handle on them, we can't answer the most basic questions. What companies are using nanomaterials, and where? What kinds, and in what amounts? How much of the potentially hazardous stuff is escaping into the air, water and soil? Into our food and drinks? Nobody knows.

At a February workshop on what research is needed to better understand nanorisks, speaker after speaker presented questions without answers. Rutgers University environmental scientist Paul Lioy, assigned to talk about human exposures to nanomaterials, was especially blunt.

"This is basically virgin territory," he said. "The fact that it's virgin territory is not good for the field, and it should be fixed really quick."

Big Benefits, Big Risks?

Nanomaterials are not new. Some exist naturally, and others result from combustion--like the ultrafine particles in diesel exhaust that have been linked to respiratory and heart diseases.

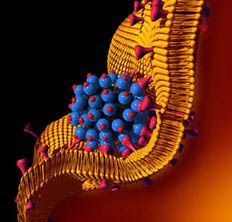

What's new is nanotechnology, the ability to manufacture and manipulate minuscule materials into forms such as quantum dots, spherical buckyballs, and cylindrical carbon nanotubes. These engineered nanomaterials take on unusual properties: changing color, for example, or becoming electrically conductive, or penetrating cell walls. And they have many uses. Carbon nanotubes, or CNTs--made by rolling up sheets of graphite just one atom thick--are extremely light and strong; they show up in high-end tennis rackets and bicycle frames. Nanosilver is used as an antimicrobial agent in everything from paint to toothpaste to teddy bears. Nanometal oxides are blended into ceramics and coatings, making them more durable.

While there's no universal definition, the "nano" moniker generally covers materials between one and 100 nanometers. A nanometer is one billionth of a meter, or between 50,000 and 100,000 times thinner than a human hair.

Nanotech offers enormous potential benefits. Medical researchers are investigating ways to use nanomaterials to target tumors and then deliver tiny amounts of drugs directly inside the cancer cells, sparing the healthy cells. Possible green tech applications include cheaper, more efficient solar panels and water-filtration systems, energy-saving batteries and lighter vehicles that use less fuel.

That's the upside. But exciting new wonder materials often reveal a dark side, too. Asbestos--now synonymous with bankrutpcy-inducing lawsuits and slow, painful death--was once seen as a miraculous fireproofing agent that would save millions of lives. Much of its damage could have been avoided if industry and government had heeded the ample danger signs. Now, early research on the potential hazards of nanotech is producing danger signs of its own. Workers handling nanomaterials face the biggest risks. But there are concerns for consumers, too, especially with products--like cosmetics, food and supplements--that go directly on or in the body. And with potentially toxic nanomaterials washing down the drain and into the water and soil, there's reason to worry about environmental damage as well.

Yet studies on nanotech's downside are a mere nanospeck compared to the research that's being done on how this technology can benefit humanity--and corporate profits. Of $1.5 billion in federal nano spending each year, only between 1% and 2.5% goes toward studying environmental, health and safety risks. Worse, there's no national strategy for deciding what questions need to be answered, or what to do with those answers as they arrive.

Occupational Hazards

Since the 17th century, when Italian physician Bernardino Ramazzini pioneered the field of occupational medicine, researchers have looked to the workplace for advance warning of new illnesses. From janitors blinded by ammonia fumes to chimney sweeps who absorbed cancer-causing soot through their skin, workers get sick first and most acutely because of their intense, daily toxic exposures. That's why much of the still-sparse nano health and safety research has focused on the possible hazards of working with nanomaterials. Scientists can't expose workers to potential toxins and watch to see if they keel over. But if employers cooperate, researchers can find out what materials workers are using, in what amounts and forms, and under what conditions. Then they can simulate those exposures with lab animals.

Some studies find little or no risk. Others are alarming. Last year, British researchers reported that when long, straight carbon nanotubes--shaped like asbestos fibers--were injected into mice, they caused the same kind of damage as asbestos. Of course, workers wouldn't ordinarily stick themselves with a needleful of CNTs. But a follow-up study this year, by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), found that when mice inhaled CNTs, the tiny tubes migrated from their lungs to the surrounding tissue--the very spot where asbestos causes the rare cancer known as mesothelioma. One reason nanomaterials can cause trouble is that they are small enough to evade the body's defenses. In a University of Rochester study of the accidental nanoparticles known as ultrafine pollution, they bypassed the protective blood-brain barrier and slipped directly into the brain's olfactory bulb. Other research demonstrates that nanomaterials can

penetrate the deepest part of the lungs. From there, they cross into the bloodstream and various organs.

Based on evidence like this, the European Union's occupational health and safety agency issued an expert report in March, citing nanoparticles as the number-one emerging risk to workers. In the U.S., NIOSH has issued a guidance document urging employers to avoid exposing workers to nanomaterials--for example, by enclosing equipment and using ventilation to reduce dust and fumes. But NIOSH has no regulatory power; it can only suggest.

The Pig-Pen Effect

"You're producing a personal cloud of exposure," Paul Lioy warned. "Every time you breathe. Every time you move. If the materials you're wearing have [nano]materials that can be released, they will be released. It's basically the Pig-Pen effect.

Lioy, the Rutgers environmental scientist, was speaking theoretically. His audience was fellow scientists, gathered in Bethesda, Maryland, for a workshop sponsored by the federal government. The workshop's title: "Human & Environmental Exposure Assessment of Nanomaterials." Lioy's assignment: Talk about the need for research to "characterize exposure to the general population from industrial processes and industrial and consumer products containing nanomaterials." His message: There is no research on whether and how the general population is exposed to nanomaterials. Searching the scholarly literature, Lioy's associates "spent hours looking for data ... and found nothing," he said.

While workers are on the front lines of nanoexposure, Lioy cautioned against ignoring consumer exposures. "We are all in contact with it--300 million of us, if we use products that have nanoparticles," he declared. And while nanomaterials that are embedded in a hard surface like a computer keyboard are probably not a big worry, clothing and cosmetics might be a different story, he said. That's where his comparison to Pig-Pen, the Peanuts character forever surrounded by a cloud of dirt, comes in: the idea that every time we move, nanoparticles might come loose from our moisturizer or our stain-resistant togs.

Noting that "a lot of nanoparticle uses are terrific," Lioy said he doesn't want society to do without. As scientists do the necessary studies, "I think a lot of issues will go away," he said. "I just don't want unintended consequences."

Down the Drain

Cyndee Gruden is getting the poop on nano-pollution--literally.

One of the main environmental concerns about nanomaterials is what happens when they wash out of clothing, hair or skin and go down the drain. Do they harm aquatic life? Do they interfere with wastewater treatment?

Gruden, a civil engineering professor at the University of Toledo in Ohio, is tackling part of that last question by looking at the effects of two nanometals--titanium dioxide and zinc oxide, used in sunscreens, paint and other products--on bacteria.

Metals "can be toxic to microorganisms," she notes. "In fact, that's specifically what they're for" in consumer products: to inhibit mold, mildew and other nastiness. But when nanometals make their way to a sewage treatment plant, Gruden worries that they might harm the beneficial bacteria that break down what's delicately known in the business as "biosolids."

Her preliminary findings, which she presented at a meeting of the American Chemical Society (an academic group, not an industry organization) in March, are mixed. Nano-titanium dioxide damaged bacteria, causing cell walls to break at "relatively low concentrations," similar to what you might see at a sewage treatment plant, Gruden says in an interview. But "in terms of function, what does that mean? Are the bugs able to do what they're supposed to do?"

To answer that question, she added some biosolids to her test tubes and measured how much methane the bacteria produced as they digested for five days. The titanium dioxide didn't seem to slow the bugs down; in fact, methane production actually increased. But when Gruden added nano-zinc oxide, gas production slowed down. She's running more experiments this summer to see what happens when the bacteria are exposed to the bugs for a full 30 days.

"The take-home message for me is, the behavior of these particles is very complex," Gruden says. "When you take a nanoparticle and put it into the environment, you have to know how it's going to behave. And we don't."

One metal Gruden didn't look at is nanosilver, widely used as a microbe-killer. The Project on Emerging Nanotechnologies, a nonprofit research and advocacy organization funded by the Pew Charitable Trusts in Washington, D.C., maintains an inventory of more than 800 consumer products advertised as using nanotechnology. Silver is by far the most frequently identified material.

In an experiment publicized last year, Arizona State University graduate student Troy Benn bought nanosilver-containing socks off the Internet and simulated washing them in jars of water. He found that, for several brands, most or all of the silver disappeared in just a few washings. Silver has been used to kill bacteria since ancient times, when the Greeks found that wine stayed fresh longer in vessels lined with the precious metal. It's potent enough that the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) regulates silver as a pesticide. Which raises the question: What does nanosilver do to the "good bugs" downstream, at the sewage treatment plant and elsewhere?

In 2006, a trade organization of wastewater treatment operators was concerned enough about a new silver-ion-emitting Samsung washing machine to pressure the EPA to include such equipment under its pesticide rules. The EPA responded by cracking down, not only on the washer but also on manufacturers of products advertised to contain nanosilver, including a line of supposedly sanitary computer peripherals. Separately, a coalition of consumer, health, and environmental groups filed a petition last year asking the EPA to impose a moratorium on nanosilver products until more safety research is done. In addition, the EPA has awarded a grant to Arizona State researchers to investigate interactions between various kinds of nanomaterials and wastewater biosolids.

Oversight or Overlooked?

In the U.S., the EPA has emerged as the lead agency on nano oversight. But that's not saying much. It is wrestling with the possible risks of nanomaterials, but so far has taken almost no action to regulate them.

In a voluntary Nanoscale Materials Stewardship Program, the EPA asked companies to submit information about what nanomaterials they're using. Very few did, and even the companies that participated withheld large amounts of data as business secrets. This March, the EPA began requiring manufacturers of carbon nanotubes to file pre-manufacturing notices under the Toxic Substances Control Act. California is requiring carbon nanotube makers to share their environmental, health and safety test data with the state, and is considering imposing the same mandate on makers of nanometal oxides, like the ones Gruden is testing.

But the EPA is not the only federal agency with responsibility for nanomaterials. Cosmetics, sunscreen, and food and beverages--which fall under the jurisdiction of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)--make up roughly 30% of PEN's consumer products inventory. Yet the FDA is poorly equipped to ensure the safety of nano-containing dietary supplements, according to a 2008 report by two former agency officials. (Friends of the Earth has urged mandatory labeling of nanofoods and a moratorium on nano-containing cosmetics until they're shown to be safe.) The Occupational Safety and Health Administration, which is responsible for protecting workers, has not even begun to work on nano rules.

A former EPA official, J. Clarence Davies, proposes merging all these agencies and more into a new Department of Environmental and Consumer Protection. A "scientific agency with a strong oversight component," it would cover products, pollution, workplace health and safety, climate change and health effects of nanotechnology as well as other technologies, Davies writes in his April 2009 report, "Oversight of Next Generation Nanotechnology."

Outside the U. S., regulators are taking a somewhat more precautionary approach. Still, governments have adopted very few nano-specific rules to protect people or the environment. But there are bright spots. At Rice University in Houston, Texas, for example, Vicki Colvin and her colleagues are trying to engineer nanomaterials that are safe from the get-go, rather than looking for ways to minimize harm from nanotoxins.

But fears abound that the teeny genie is escaping from its bottle. The asbestos parallel causes particular concern--prompting the Australian Council of Trade Unions, for example, to call for that country to adopt nano regulations by year's end. At the Bethesda workshop in February, Harvard industrial hygienist Robert Herrick advocated an all-out effort to gather information about nano exposures and possible related illnesses. The asbestos industry could have undertaken a similar effort in the 1930s, he noted. Instead, industry execs decided to keep the subject quiet. If they had gone the other way, Herrick wondered, "how different would history be?"

.....

Carole Bass, a journalist, writes about the environment, workplace health, legal affairs and other subjects.